On a frigid night in January 2019, Carlie Beaudin finished up with her cancer patients at Froedtert Hospital shortly before 1 a.m. The 33-year-old nurse practitioner pulled on her winter coat, wrapped her red scarf around her neck and headed to her car.

She rode the elevator down to Level Two in the underground parking garage. As she made her way to her Toyota Rav4, a man stepped out from behind a concrete pillar. Beaudin stopped briefly as he said something to her; then she kept walking.

When she got to her car, the man — a stranger who had once been a valet at the hospital — ran up and tackled her. He kicked her and stomped on her head and body more than 40 times. Then he pulled her into her car and drove to the snowy rooftop of a parking garage next door, where he dumped her out and drove over her. Somewhere along the way, he also choked her.

The attack carried on for six minutes, captured by surveillance cameras. In fact, cameras had recorded the man before the attack, lurking around the hospital and hiding behind pillars for two and a half hours.

But Froedtert’s security team had failed to act.

Beaudin lay in the cold, unnoticed by anybody at Froedtert for nearly three hours, until a snowplow driver spotted her wedged under her car, her body frozen to the ground. She was taken to the emergency room, where she was declared dead.

The COVID-19 pandemic has rallied extraordinary support for health workers: Billboards, yard signs and TV commercials have honored their sacrifice. But the less obvious risk to their well-being — violence at work — has persisted long before the pandemic and has been repeatedly overlooked by hospital administrators, regulators and lawmakers, an investigation by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel has found.

The nation's 5.2 million hospital workers are especially vulnerable, not just inside caring for the sick and injured but as they come and go to work. Made up of about 80% women, their shifts begin and end at all hours of the night, and their employers often require them to park in faraway lots and poorly lit garages.

Even as health care companies have taken in billions in revenue, with some recording record profits, hospitals across the country have frequently allowed parking garages to go unstaffed, cameras unmonitored and nurses to fend for themselves, documents and interviews show.

“I would literally look left and look right and then run to my car,” said Tierney Flynn, a nurse who worked at Columbia St. Mary’s on Milwaukee’s east side from 2017 until February.

In Omaha, Nebraska, three months before Beaudin was beaten to death, a nurse in her early 20s was assaulted by a stranger with a gun in a hospital parking lot. Like the attack at Froedtert, surveillance video showed the perpetrator was able to linger around the hospital undeterred by security. Before the attack, nurses had repeatedly complained to supervisors about safety in the area.

And three months after Beaudin was killed, a nurse in Dallas was robbed at gunpoint in a hospital parking lot. Like her counterparts in Omaha, she had complained weeks earlier about the lack of security in the lot.

Mawata Kamara has been a registered nurse since 2008 and spent five years traveling among hospitals across the country.

“They don’t say anything in nursing school that prepares us for the violence,” said Kamara, who now works in the San Francisco Bay area.

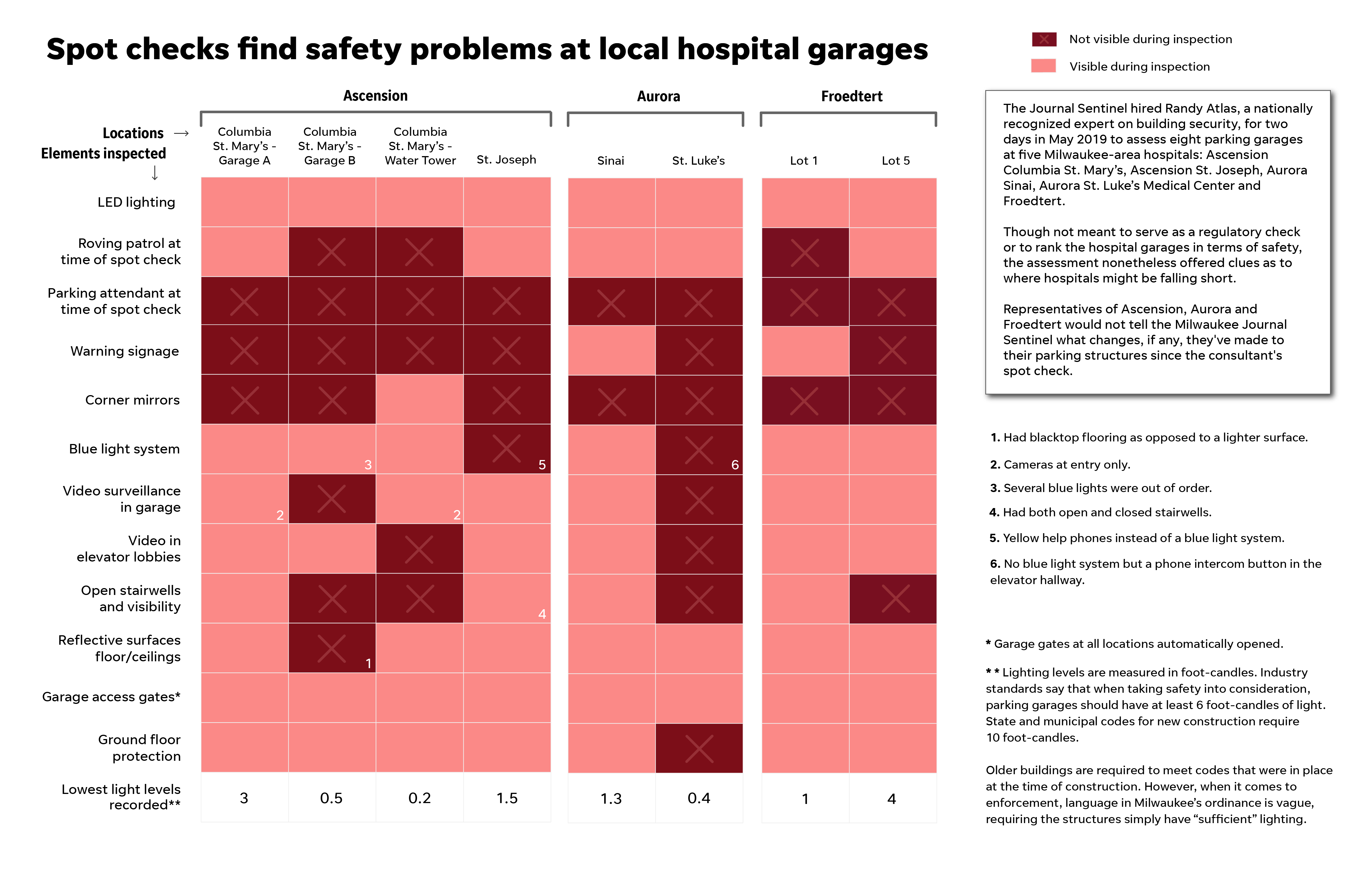

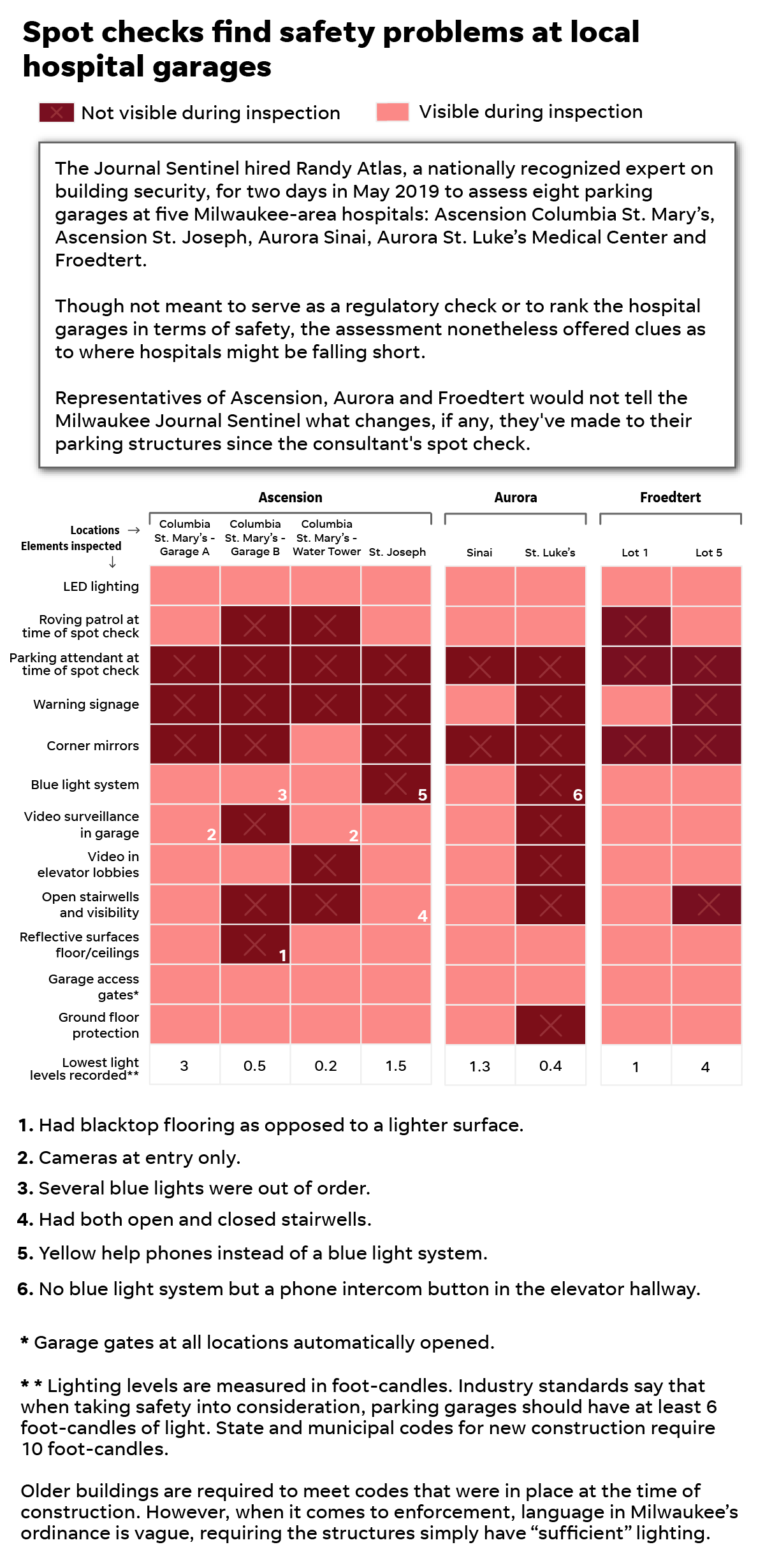

To assess the safety of hospital parking garages in the Milwaukee area, the Journal Sentinel hired a Florida-based security and crime prevention expert to examine eight structures. His spot check — over two days in May 2019 — found basic safety and security shortcomings at every one of them.

At Ascension Columbia St. Mary’s Hospital on Milwaukee’s east side, lighting levels in some spots were 30 times lower than industry standards.

A Journal Sentinel reporter also conducted one-hour checks of the parking garages in February to see if they had guards at entrance booths and how often security officers patrolled at night. At Aurora St. Luke’s, no security came through during the check. Downtown at Mount Sinai Hospital, 57 minutes passed before a patrol drove by.

Representatives from Froedtert and the other hospitals tested by the Journal Sentinel said they have multiple layers of security and that the safety of patients, visitors and employees is their top priority. None would agree to interviews or answer questions about specific policies.

“Froedtert Hospital continues to develop an environment of safety that applies across departments and touches on all of our interactions with staff, patients, and visitors,” spokesman Stephen Schooff wrote in an email to the Journal Sentinel.

In November, Froedtert reached an out-of-court settlement with Beaudin's husband, Nick, for an undisclosed amount.

Many state and local lawmakers and regulators have not addressed the hazards, failing to pass legislation requiring workplace violence prevention programs and neglecting to enforce lighting codes. Code enforcement officers from Milwaukee, Waukesha and Wauwatosa, where Froedtert is located, said they could not recall ever citing a parking garage owner for insufficient lighting.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which is charged with protecting the nation’s workforce, has done little to enforce the requirement that hospitals, like all employers, provide safe workplaces. The agency’s guidelines for parking-area safety are voluntary, and the agency issued just 18 citations from 1991 to 2014 to health care employers for failing to address violence on their campuses.

Nobody can say exactly how many have been killed and harmed in hospital parking garages. No federal agency tracks these numbers; data from local law enforcement are often incomplete and imprecise, and many hospitals themselves don’t compile the figures.

In California, the only state to track and publish detailed data on hospital violence, health care workers were victims of 218 “violent incidents” in their parking areas from July 2017 to December 2019, according to the state’s OSHA unit.

Hospitals in most states are not required to release information about violence on their properties. As a result, it’s difficult for the public and workers to hold hospitals accountable for the violence.

And nurses and other health care workers — who now make up America’s largest workforce — continue to be victimized.

“Some of the most exposed people in the world are nurses getting off on the midnight shift,” said David Salmon, a security expert with Texas-based OSS Law Enforcement Advisors, who specializes in parking safety. “You talk about vulnerability.”

“Predators love to prey on hospitals,” Salmon said.

‘Please, I am begging of you’

Mary Ball felt it in her gut when she pulled into the Parkland Hospital parking lot in north Dallas. Something wasn’t right. It was about 6:35 p.m, and the sun was low in the April sky.

The three young men standing on the nearby sidewalk seemed like they were looking at her strangely. As she parked her Honda Accord, she paused for a beat. Her shift started in 10 minutes. She had about a third-of-a-mile walk to the hospital. She had to hustle.

She gathered her bag, stepped out of her car and locked the door. When she turned around, the three men were directly in front of her. The man in the middle reached into the front pocket of his hoodie and pulled out a gun.

Pointing it at her chest, he demanded her wallet, car keys and Apple watch. As she handed them over, two of the men got into her car. The third stood with the gun pointed at her. Then he, too, got into her car.

“I stood there in complete disbelief,” she said. “Then I realized they still had a gun and could shoot me, so I turned around and ran as fast as I could, toward the hospital.”

Ball’s car was found later that evening smashed into a pole in south Dallas. Police caught two of the men but not the third.

What is particularly noteworthy about the carjacking last year is what happened less than an hour afterward.

While sitting in the hospital’s police station, Ball emailed senior executives of Parkland Hospital. “I’m with police now but I’m so upset with Parkland’s continuous lack of security for staff when this is a very high risk area and I have brought this up in the past,” Ball wrote in the email, a copy of which was shared with the Journal Sentinel. “Please, I am begging of you, what will it take to make employee safety something of significance?”

Ball had emailed nursing supervisors several months before the carjacking wondering why there seemed to be fewer security guards around the parking areas. The 38-year-old said in an interview with the Journal Sentinel that she was told that the hospital’s police department was short-staffed and that they had been shifting more officers to the emergency department.

As she filed her police report, officers informed her that the cameras in the hospital’s parking lot were not working at the time she was robbed. Ball had known the gate to the employee parking lot had been broken for weeks, opening for anybody who pulled up; now she was learning the cameras were not functioning.

“I was livid,” Ball said.

Later that night, Ball received an email response from Judy Herrington, the hospital’s vice president of medicine services: “I am so very sorry this horrible event happened to you. Please know we will support you in any way we can in getting through this emotionally.”

The next day, Herrington emailed Ball again, saying Parkland was working on safety improvements and that the broken camera system was the fault of a construction crew.

“This was a heck of a way to realize what a blind spot it left,” Herrington wrote.

The following day, when Ball went to the hospital to meet with police, she noticed the parking lot gate was still broken.

“Sadly I could just drive in, no badge access required still,” she wrote to Herrington. “I’m so sad to see first hand that my attack has not changed precautions to keep the staff who still work there safe.”

When Ball returned a few days later, repairs still had not been made, she said.

She again emailed Herrington. “Trinity lot is still open to the public and not restricted access. It’s a real shame,” she wrote. “Employees across Parkland have reached out to me to tell me how unsafe they have felt and how they have brought this up and it’s never addressed.”

On April 15, a week after the robbery, Herrington emailed Ball, informing her that the hospital expected to resolve many of her concerns within a week or so. Herrington said the construction crew was also responsible for the broken gate.

Herrington and other Parkland Hospital representatives declined interview requests from the Journal Sentinel.

Records obtained by the Journal Sentinel show that in the year before Ball’s carjacking, hospital police responded to 12 violent assaults and robberies on the Parkland campus, including a rape.

According to Ball, in the weeks following her carjacking, Parkland added security car patrols to the parking lots, repaired the cameras and gate, and gave employees noise alarms to add to their badges.

But the added security measures did not resolve all of Ball’s concerns. She said the alarms are loud but don’t connect to the security operations center; nothing prevents the general public from walking through the Parkland parking lot anytime, and the escort service remains slow. Ball said she does not know any employee who uses it.

She said that every day, she dreads going in and leaving work. “That walk is awful,” she said.

Her fears are not unfounded. Records show that in November, seven months after Ball’s carjacking, four men pulled a knife on a 29-year-old woman at another Parkland Hospital parking area.

A double danger

Parking garages, in general, are inherently dangerous places. So are hospitals. Put the two together, and you have a potentially deadly mix.

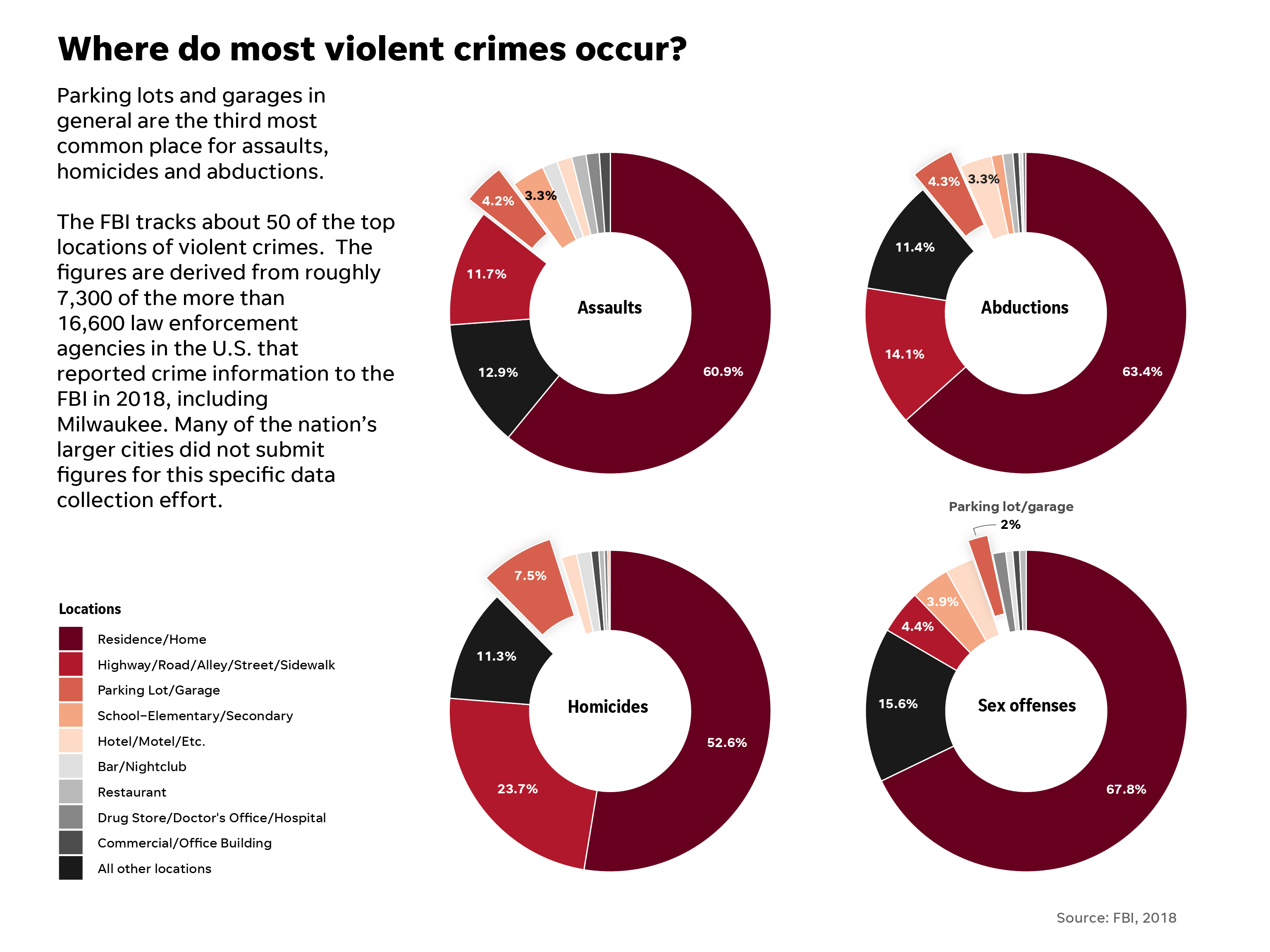

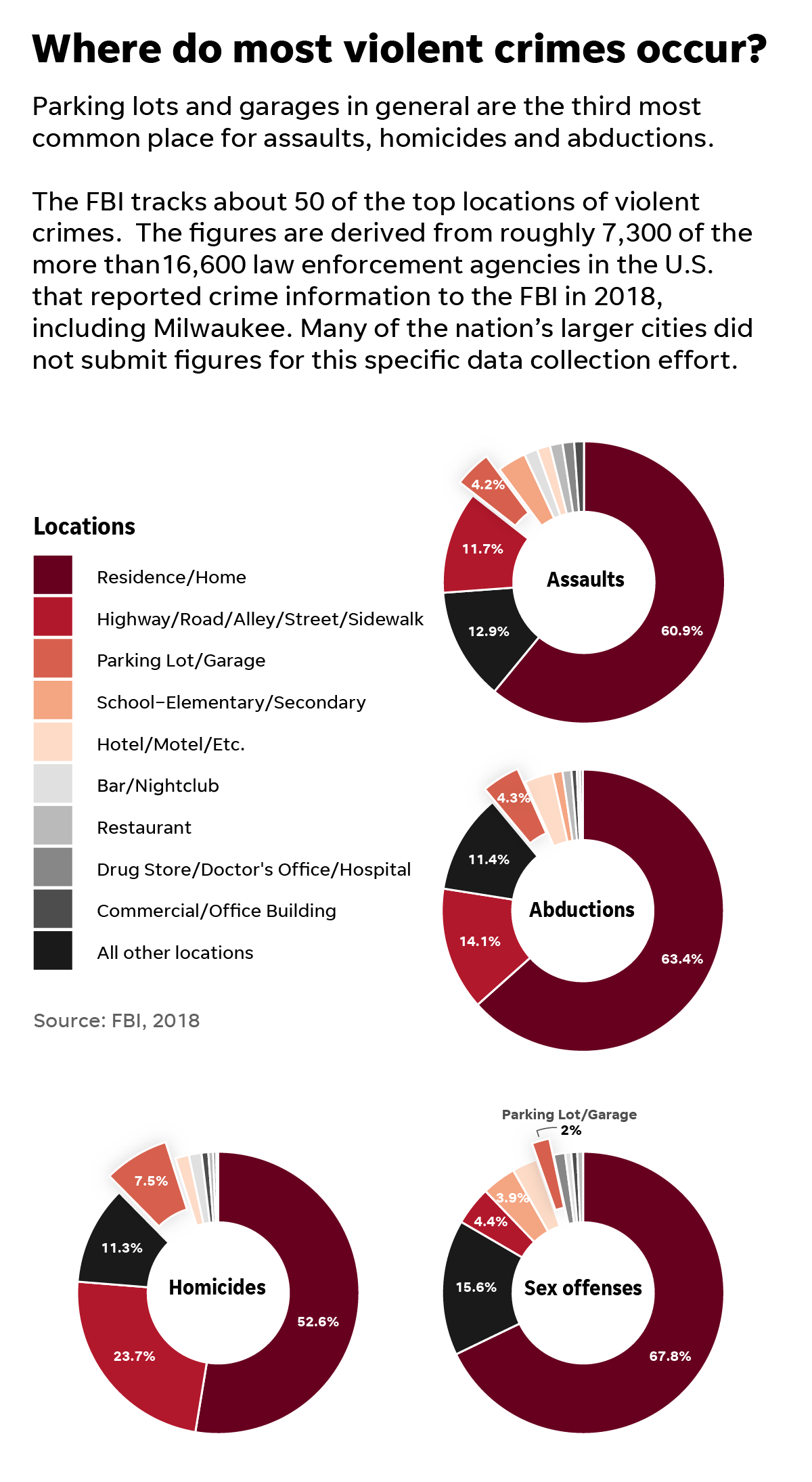

Parking garages — whether at hospitals, hotels or downtown offices — are the third most common place for assaults, abductions and homicides after private homes and streets, alleys or sidewalks, according to FBI data from 2018, the most recent year for which numbers are available.

More homicides happen in parking garages than at bars, motels, gas stations or in the woods combined, the numbers show.

“You have an indefensible position if you try to say, ‘We didn’t think it could happen here,’” said Alan Butler, former president of the International Association for Healthcare Security & Safety, the leading trade association for health care security professionals.

Crime numbers involving health care workers are equally striking: In parking areas and elsewhere on the job, the country’s 16 million health care employees are at least four times more likely on average than other professionals to be victims of workplace violence, data show.

While they help heal wounds and ease patients’ pain, they are kicked, punched, scratched, spit on, choked and otherwise assaulted at rates that far exceed any other private sector industry, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

They are injured by violence at rates that roughly equal — and in some cases surpass — those of police officers and security guards, a Journal Sentinel analysis of the labor figures shows.

And violence against health care workers is escalating, academic and industry studies show. The violent crime rate on hospital properties jumped 55% from 2015 to 2018, according to a survey by the international health care security group. Roughly nine of 10 victims were employees.

While attacks on nurses and other hospital workers more commonly take place in emergency departments, psychiatric wards and patients’ rooms, some of the more serious violence — armed robberies, abductions and rapes — often occurs in the parking and outside areas, studies show.

In California, for example, knives were wielded in less than 1% of all violent incidents, yet they were used in 10% of the cases reported in parking lots, an analysis by the Journal Sentinel found.

Hospital administrators have known about the risks in parking areas for decades.

A 1991 survey by the international health care security group found that nearly 70% of armed robberies and 56% of rapes of health care workers occurred in parking and adjacent areas. “Clearly, parking security represents a major challenge for hospitals, demanding time, personnel, equipment and dollars,” authors of the report wrote.

In the 1970s, numerous nurse abductions and slayings made national headlines.

“I felt lucky to be alive,” said Randi Olson, a nurse who in 1976 was grabbed at knifepoint from a Chicago hospital parking lot, raped and thrown in the trunk of her car. “Usually, they kill you.”

Two years after Olson’s assault — in an eerily similar case — a man pulled a gun on Linda Goldstone, a 29-year-old mom on her way to work at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago where she taught a Lamaze class. The man shoved her into his car, raped her and then forced her into the trunk. He held her captive for two days before killing her.

“It’s a longstanding problem, and it’s getting worse,” said Michelle Mahon, a nurse and spokeswoman for National Nurses United, which represents more than 150,000 registered nurses in the country. “Our entire society is under stress, and the hospital is often the place where these stresses converge.”

Tests show light below standards

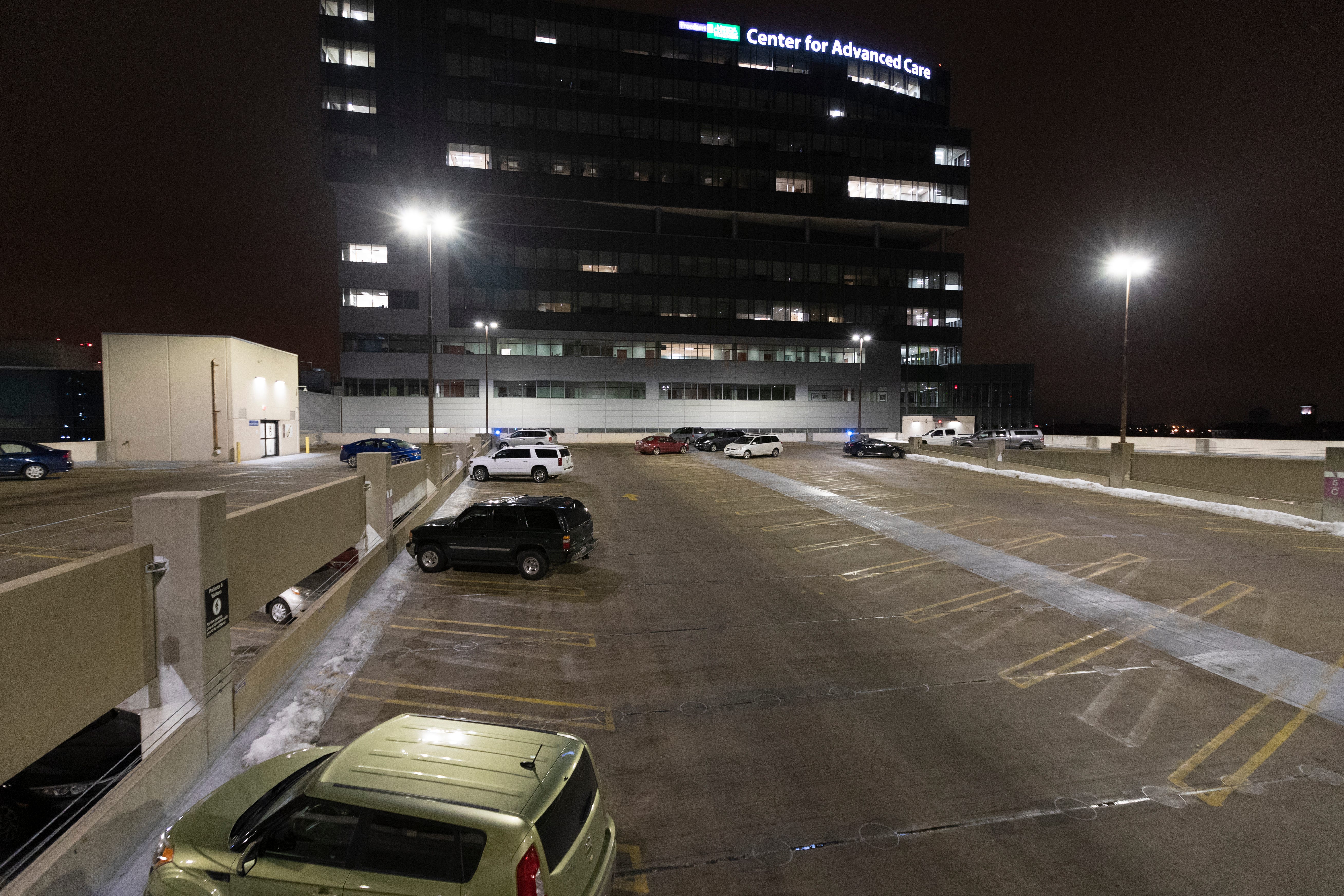

Level Two of Froedtert’s Parking Garage 5 looked fairly well-lit on a crisp night in May 2019, about four months after Carlie Beaudin was beaten to death.

Randy Atlas walked around the murder site holding a gadget that looked like an electric razor. But it was a light meter, measuring lighting in “foot-candles.”

A foot-candle is the amount of light equivalent to what a candle would illuminate in a 1-square-foot area. The lighting level inside most big-box stores, for example, measures about 30 foot-candles. Movie theaters register about 0.5 to 1.

Lighting is universally considered among the most important security features in parking garages. Yet state and municipal codes vary widely. Some require just 1 foot-candle, which is an industry standard aimed only at ensuring motorists can navigate the area.

Taking safety into account, the International Association for Healthcare Security & Safety, with more than 2,000 members worldwide, recommends parking garages have at least 6 foot-candles of light. Some municipalities, such as Milwaukee and Wauwatosa, have more stringent requirements, mandating new garages be constructed with a minimum of 10 foot-candles.

Older buildings are required to meet codes that were in place at the time of construction; however, when it comes to enforcement, language in Milwaukee’s ordinance is vague, requiring the structures simply have “sufficient” lighting.

As Atlas made his way through several hospital garages in the Milwaukee area, all failed to meet industry standards or modern-day municipal codes, according to his measurements.

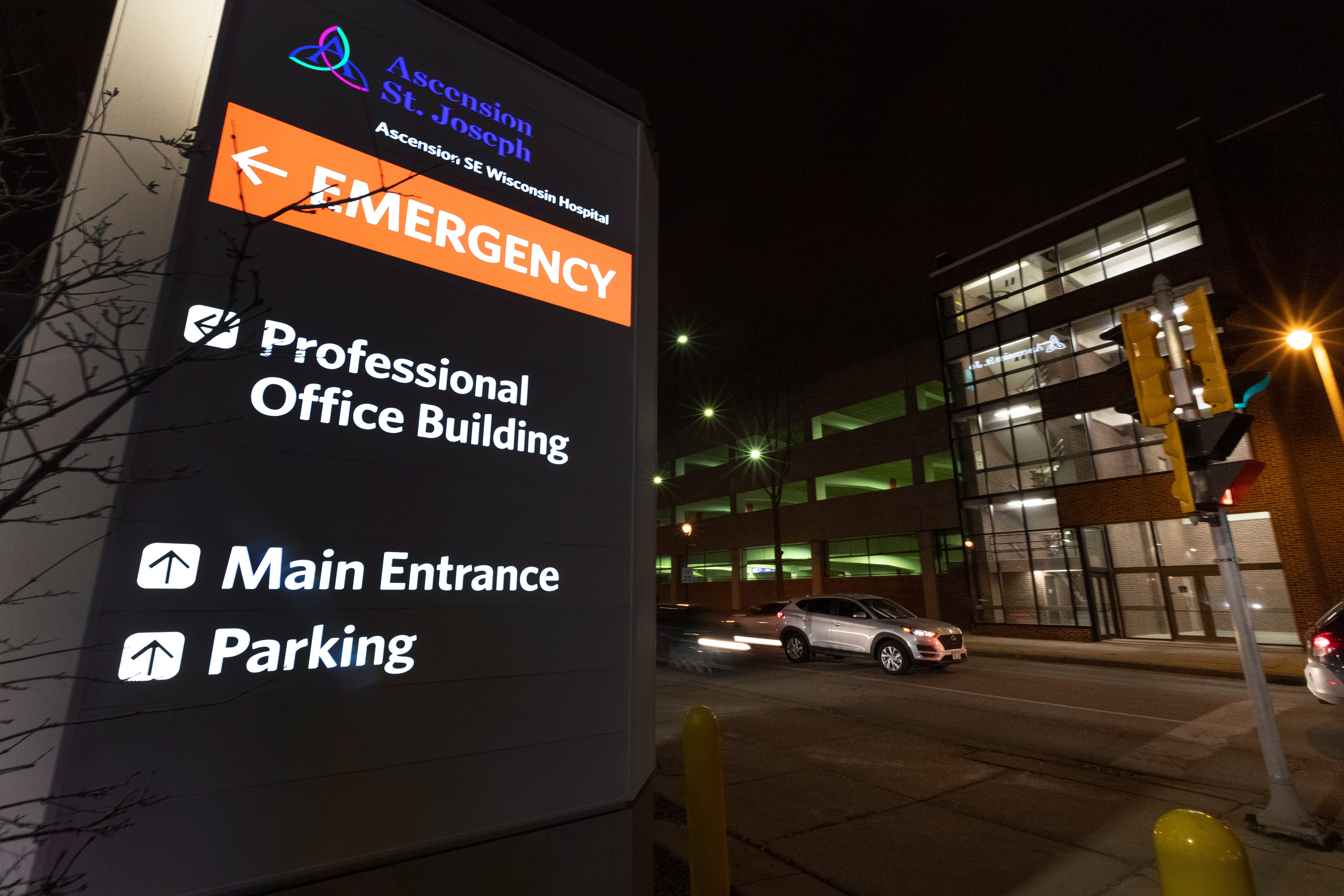

The Journal Sentinel hired Atlas, a nationally recognized expert on building security, for two days to assess eight parking garages at five Milwaukee-area hospitals: Aurora Sinai, Ascension Columbia St. Mary’s, Ascension St. Joseph’s, Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital and Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center.

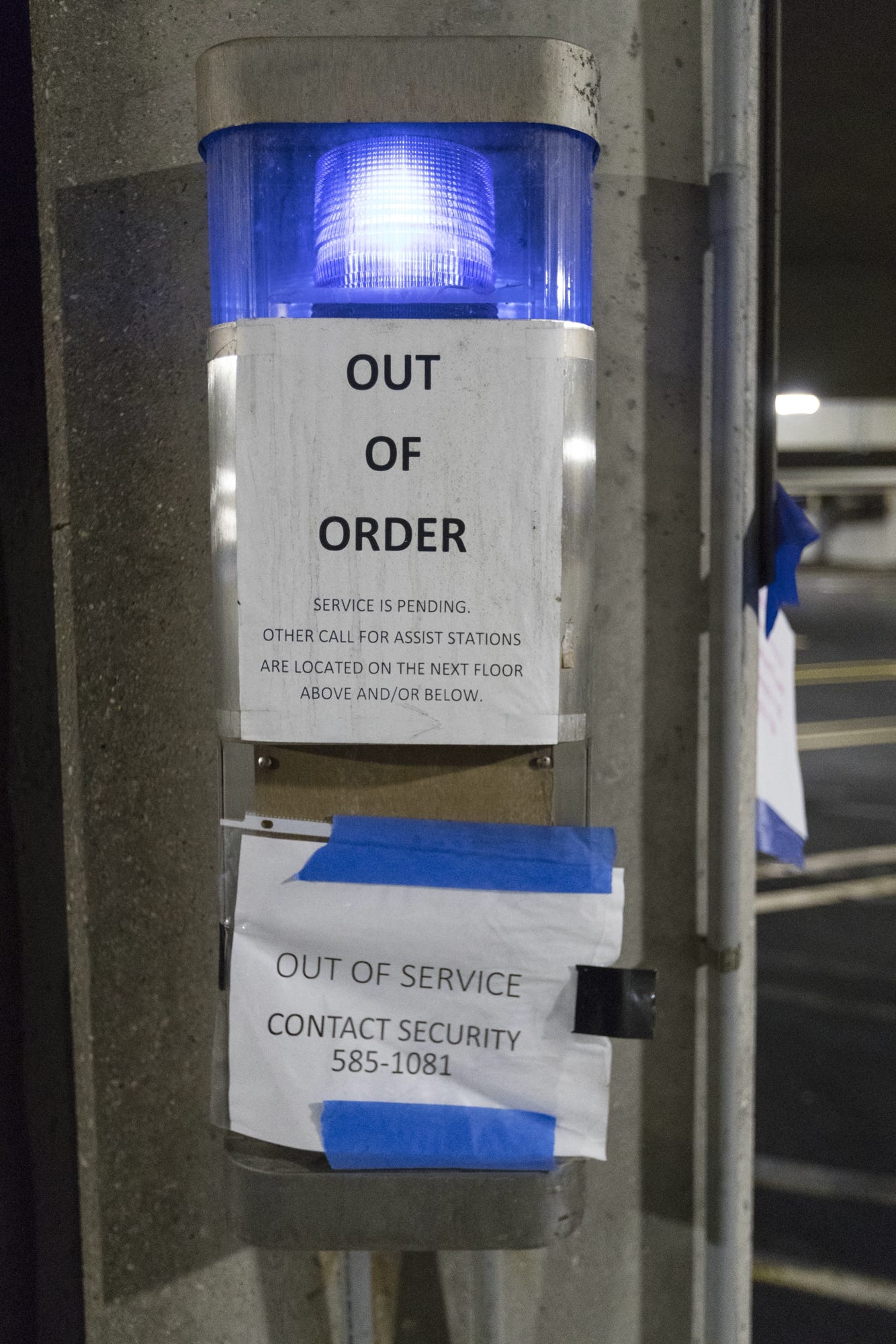

Accompanied by a reporter and photographer from the Journal Sentinel, Atlas assessed lighting in each garage and other safety factors. He looked for surveillance cameras, noted whether a parking attendant or a security patrol was on-site, checked for corner mirrors and emergency call boxes, and gauged access points and stairwell visibility.

Though not meant to serve as a regulatory check or to rank the hospital garages, the assessment nonetheless offered clues as to where hospitals might be falling short.

On this May night, Level Two of Froedtert’s Garage 5 where Beaudin was attacked initially looked fine, Atlas said. Video surveillance was well-placed, and Atlas noticed motion-activated light sensors and blue light emergency call boxes. A roving security vehicle passed through while he was walking around.

But Atlas found an important design flaw with the garage: wide concrete columns providing plenty of hiding spots for people with ill intent.

And when Atlas held the light meter in the aisles where the cars were parked, the lighting measured between 4 and 6.5 foot-candles — well short of Wauwatosa’s requirement of 10.

But neither Wauwatosa nor the City of Milwaukee inspects parking garages for compliance with lighting, other than for emergency and exit lights, which fall under fire codes, officials with both cities said.

Inspectors typically visit when they receive complaints, said Mike Mannan, manager of building code enforcement for commercial properties for the City of Milwaukee. And usually, the complaints are from neighbors of buildings with too much lighting, Mannan said.

“We don’t have the staffing to go through every parking garage to see if there’s adequate lighting,” he said.

It’s unclear what the conditions were the night Beaudin was killed. Froedtert won’t say what specific improvements, if any, to the two parking garages were made following her death.

Atlas’ spot check found problems at the other garages. Two of Columbia St. Mary’s garages on Milwaukee’s east side, including where a woman was stabbed by a stranger more than a dozen times in 2018, had inconsistent and shadowy lighting.

“We’re looking for even distribution,” Atlas said. “Not brightness back to darkness. Your eyes can’t adjust, and you can be easily ambushed.”

One of the garages, built in the mid-1970s, registered just 0.2 foot-candles in some spots near the cars, far below the industry standard of 6 and Milwaukee’s modern-day standard of 10.

“If we’re looking at a garage with two-tenths of a foot-candle, that’s about half the light of a full moon," Atlas said. "It’s dark."

Representatives from Columbia St. Mary’s would not answer questions from the Journal Sentinel, responding only with a statement via email.

“Our campuses have a combination of 24/7 cameras and garage patrol services, emergency call systems, security escort services and enhanced LED lighting,” a spokeswoman wrote. “We review and strengthen our safety operations regularly as part of our commitment to the wellbeing of the communities we are privileged to serve.”

Atlas’ overall assessment of Milwaukee’s hospital garages: average in terms of security-focused environmental design but troubling in terms of lighting.

“There were areas that were very dark, and some of the readings we found proved that,” he said.

‘You take your chances’

In the wake of a serious crime in a parking garage, hospitals typically fix broken lights, install more cameras, add roving patrols, offer to escort workers to their cars and send emails reminding staff to walk in groups or pairs.

But the added safeguards are often insufficient and temporary, the Journal Sentinel investigation found.

For example, nurses from across the country repeatedly said in interviews their hospitals’ escort programs are slow and impractical. The last thing anybody wants to do after working a long shift is wait another half-hour to get to their cars, they said.

“You’re tired. You’re ready to go," said Yvette Harris, a registered nurse from Riverside, California. "You take your chances, and you pretty much pray.”

Two nurses at Creighton Bergan Mercy Hospital in Omaha said that well before their co-worker was assaulted at gunpoint in 2018 they had complained repeatedly to supervisors about having to walk alone — often late at night past a bus stop where drug users commonly hung out — to get to their designated parking area.

“This is a daily issue for nurses: Am I going to get mugged in the parking lot?” said one of the nurses, who did not want her name published out of fear of retribution by the hospital. Another nurse at the same hospital said security remains sparse more than a year after their co-worker’s assault. “Not sure where [the security guards] are half the time and not a heck of a lot of light in some areas,” she said in a written message to the Journal Sentinel.

Creighton Bergan Mercy Hospital representatives did not respond to phone calls and emails from the Journal Sentinel.

Despite mounting pressure from nurses and others in the industry, fewer than a dozen states have adopted legislation requiring health care employers to develop policies aimed at preventing workplace violence. Wisconsin is not among them.

In California, nurses ramped up pressure on state legislators in 2010 after a patient hit a nurse in the head with a lamp, killing her. New laws now require health care employers to track violent incidents, identify risk factors, develop violence prevention plans and train workers.

“This was a campus that had three security guards on the whole campus,” said Renee Altaffer, a trauma nurse in the intensive care unit at Sutter Health in Roseville, California. “We had almost nothing in place to prevent something from happening.”

The hospital added more than a dozen security guards, fixed call boxes, upgraded cameras and implemented a visitor-check-in system, Altaffer said. “We think everybody should be doing this.”

In Philadelphia, nurses at hospitals in the Jefferson Health-Northeast chain were so afraid of the garages that they were parking on the street, said Michelle Conley, the chief nursing officer for the chain.

Conley said she and the hospital’s security director held listening sessions with staff and got an earful. “We took a beating,” Conley said. “I hadn’t understood the magnitude.”

As a result, the hospital invested about $1 million on improvements, including upgrading lighting and adding cameras, panic buttons and golf carts to escort employees to their cars, she said.

After decades of inaction by Congress, the U.S. House of Representatives in November passed a bill that would require OSHA to mandate all hospitals and health care employers to implement workplace violence prevention programs.

The bill is in the Senate, but it’s opposed by the American Hospital Association, a lobbying organization with a membership of about 5,000 hospitals and health care facilities. The association argues its members already have adequate safety programs in place.

Although it’s unclear how many hospitals actually have formal workplace violence prevention programs, data from the hospital association show that as of 2018 nearly half did not.

Often there isn’t much incentive, said Butler, of the international health care security trade group. “Security as a whole does not generate revenue for an organization,” he said.

OSHA has long recognized the danger health care workers face. In 1996, the agency issued guidelines to help employers create workplace violence prevention programs, including in parking areas. Yet the guidelines have remained voluntary.

From 1991 to 2015, OSHA inspected an average of just 14 hospitals and health care facilities per year for workplace violence issues, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of Congress.

In Oregon, one of the few states that has adopted workplace violence prevention laws, the state OSHA department issued just eight fines over the last decade for violations related to workplace violence in health care institutions.

In one Oregon case reviewed by the Journal Sentinel, employees at a psychiatric hospital were assaulted nearly 300 times in a seven-month period in 2017. The state OSHA department found the hospital was not properly logging and investigating all the assaults.

The agency fined the hospital $1,650 — or $5.50 per assault.

Unanswered questions

In the case of Carlie Beaudin, the nurse practitioner found murdered and frozen to the parking garage pavement, the amount was $0.

OSHA did not cite Froedtert Hospital or the Medical College of Wisconsin, which technically employed her.

The agency provided limited records to the Journal Sentinel, withholding or blacking out many portions of the investigative file. In the documents OSHA did supply, investigators didn’t address key issues of the murder that were raised by other authorities.

For example, the Milwaukee County medical examiner’s report says the man accused in Beaudin’s homicide was “lurking around various places” on the hospital grounds for two and a half hours before the attack, including more than an hour in the parking garage.

OSHA’s records make no mention of that or ways Froedtert might have intercepted him.

The district attorney states in the criminal complaint against the man that the snowplow driver who first found Beaudin beneath her car sought help via an emergency intercom system near the parking garage elevator but got no response.

OSHA’s records say the emergency alerting/alarm systems were functional at the time of the murder. The documents do not state why nobody responded when the snowplow driver called for help on the intercom.

Although OSHA inspectors reported that some of the hospital’s 700 cameras across its campus are not monitored in real-time, inspectors failed to address how that might place workers at risk. The camera that recorded the six minutes during which Beaudin was beaten to death was not being monitored at the time, according to the OSHA records.

The inspectors noted that after the slaying, Froedtert stationed a security officer at each of the parking garages and lots. “It is unknown at this time if this practice will be maintained in place permanently,” an inspector wrote.

Froedtert would not tell the Journal Sentinel whether the practice remains in place.

Federal OSHA investigators said the hospital and the college had comprehensive written workplace violence programs.

OSHA officials would not answer questions from the Journal Sentinel about the investigation.

Victor Harding, an attorney representing Carlie Beaudin’s husband, Nick, called her death preventable. He said some of the surveillance cameras are “essentially scarecrows” and that a more sophisticated video system could have helped.

Security experts say software exists that can detect odd motions, such as when a person is bobbing up and down while peering in car windows, and then alert security. Froedtert would not comment on whether improvements have been made to the hospital’s video surveillance system since Beaudin’s death.

The attorney also said that the attacker was not required to sign in to the hospital when he arrived. Security experts agree that controlling access to hospital grounds is critical. They recommend that hospitals, like some public schools, require visitors to sign in and wear a badge with their picture.

“If people have ill-intent, and they realize that their photo ID is going to be taken, that will give them a second thought,” said Bryan Warren, a health care security consultant who has done work for Froedtert unrelated to Beaudin’s death.

Following Beaudin’s death, Froedtert began requiring visitors to check in and get passes during the overnight hours, according to Schooff, the hospital spokesman.

Kenneth Freeman, the man charged in Beaudin’s death, was found guilty in February of committing the homicide and at the same time not legally responsible due to mental disease. He was ordered to be committed to a mental health facility for life without the possibility of extended supervision.

Beaudin's husband, a 35-year-old accountant, said in an interview from his Greendale home that it’s not good for his health to focus on how Carlie’s death might have been prevented. “If I were to find a good answer, what would that do to me?”

He and Carlie had been married for nine years. They had no children but were undergoing intrauterine fertilization. He said the couple had some early promising results but had been repeatedly disappointed.

Shortly after her murder, Beaudin learned from doctors that the autopsy conducted on his wife had found elevated levels of certain hormones in her blood. Those levels could have been caused by a fertility treatment.

Or, the doctors said, it could have meant that she was finally pregnant.